Former Florida Governor Jeb Bush initiated the Florida Pregnancy Support Services Program through executive order in 2004 as Florida’s “Alternative to Abortion” program. The order authorized the use of public funds for anti-abortion pregnancy centers that push people away from obtaining abortion care.

History of Anti-Abortion Pregnancy Centers

Beginning in the 1960s, the anti-abortion movement founded what they called “crisis pregnancy centers” in response to the widespread legalization of abortion access. The movement established these centers across the country to entice pregnant people seeking abortions to enter their doors where employees or volunteers try to convince them to forgo the intended procedure. Anti-abortion pregnancy centers sometimes offer some version of health care services including ultrasounds, pregnancy tests, and testing for sexually transmitted diseases, but administration of these services is not their primary mission. Many advocates, lawmakers, and public officials who support reproductive rights have concluded that these centers purposefully mislead people in violation of state laws.[1]

Anti-abortion advocates claim that Robert Pearson, a homebuilder, set up the first such center in Hawaii in 1967.[2] After the Supreme Court affirmed the right to abortion in 1973, the anti-abortion movement expanded its efforts to set up these centers designed to divert pregnant people away from medical clinics that provide abortion care.

For several decades, anti-abortion pregnancy centers survived by raising funds from religious donors and churches. After establishing the first center in Hawaii, Mr. Pearson started the Pearson Foundation in 1969 in St. Louis, Missouri to promote similar centers nationally. An early manual published by the foundation instructed centers to lie about their true purpose. The manual explained that anti-abortion pregnancy centers should employ dual names and separate marketing materials with one brand intended to “draw abortion-bound women” and another to attract donors. Several state attorneys general investigated these centers and found that this dual structure was set up to mislead people and violated consumer protection laws.

By 1985, Birthright – a Toronto-based network of anti-abortion pregnancy centers claiming to be the oldest in North America – claimed a network of more than 600 centers throughout the continent. At the time, Alternatives to Abortion International listed 1,500 operating centers. Growth exploded throughout the decade. In 1989, Newsday reported that 4,000 centers existed in the United States.[3] The industry is dominated by a few national players, including Heartbeat International and Care Net, each of which claim thousands of affiliates.[4]

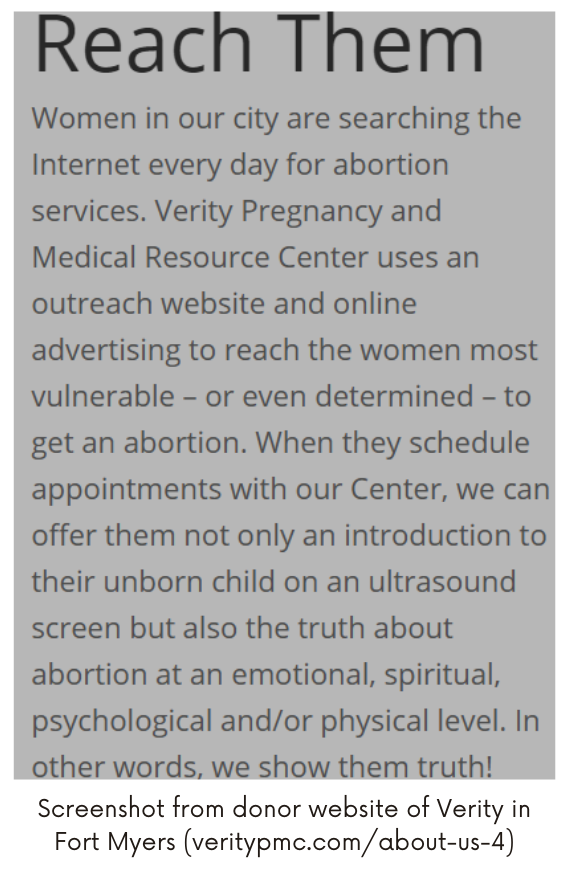

These centers are typically organized around religious principles and pay for their operations by raising money from private donors, foundations, and churches.[5] Despite investigations by state officials, anti-abortion pregnancy centers continue to employ the same misleading tactics they have used for decades. They often locate their centers as close as possible to real medical clinics that provide legitimate health care services. They advertise in the same places as abortion providers and use innocuous language to lead pregnant people to believe they also provide abortions.

Anti-abortion pregnancy centers have updated their tactics for the digital age. For instance, they maintain dual websites: a secular site to appeal to pregnant people and a religious one to appeal to their donors and supporters. Centers have also hired digital advertising firms to push geotargeted ads at people who enter

abortion clinics. The Massachusetts Attorney General concluded that this tactic violated consumer protection laws and forced one advertising firm to forgo this approach in Massachusetts.

Anti-abortion pregnancy centers around the country began pursuing government funding in the late 1990s after Pennsylvania funded a network of centers through the first Alternative to Abortion Program, Project Women in Need. States attempt to offer parenting assistance and material goods through an Alternative to Abortion Program by granting money to organizations that promote childbirth, but often these states settle for granting money to anti-abortion pregnancy centers that manipulate pregnant people from accessing the care they seek. As of 2019, 14 states fund anti-abortion pregnancy centers through some variation of an Alternative to Abortion Program. Through increased political involvement and advocacy, using affiliations with national organizations, they have secured more government funding across the United States at the state and federal level. Fourteen states fund anti-abortion pregnancy centers through various versions of the alternative-to-abortion programs, while more than 3,700 centers operate across the U.S.[6] Currently there are 192 centers operating in Florida.

[1] Tom Bowman, Crisis Pregnancy Centers Accused of Misleading Women Seeking Abortions, The Baltimore Sun (Jul. 25, 1991), available at https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1991-07-25-1991206027-story.html; Joanne D. Rosen, The Public Health Risks of Crisis Pregnancy Centers, Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, Volume 44, Issue 3 (Sep. 10, 2012), available at https://www.guttmacher.org/journals/psrh/2012/09/public-health-risks-crisis-pregnancy-centers; Jane Gross, Pregnancy Centers: Anti-Abortion Role Challenged, The New York Times (Jan. 23, 1987), available at https://www.nytimes.com/1987/01/23/nyregion/pregnancy-centers-anti-abortion-role-challenged.html.

[2] Judith Davidoff, Pregnant? Scared?, ISTHMUS (Jan. 31, 2013), available at https://isthmus.com/news/news/pregnant-scared-abortion-risks-are-exaggerated-at-wisconsins-crisis-pregnancy-centers/; Crisis Pregnancy Centers: An Affront to Choice, National Abortion Federation (2006), available at http://prochoice.org/wp-content/uploads/cpc_report.pdf.

[3] Mark Lowery, Abortion in America. Focus on the City; An Alternative That’s Not Always Made Clear, Newsday, April 25, 1989.

[4] Our Story, Heartbeat International (last accessed Nov. 17, 2020), available at https://www.heartbeatinternational.org/about/our-story; Affiliation, Care Net (last accessed Nov. 17, 2020), available at https://www.care-net.org/affiliation.

[5] Financial Accountability, Heartbeat International (last accessed Nov. 17, 2020), available at https://www.heartbeatinternational.org/about/financial-accountability; Financial Information, Care Net (last accessed Nov. 17, 2020), available at https://www.care-net.org/financial-information.

[6] Swartzendruber A, Lambert DN. A Web-Based Geolocated Directory of Crisis Pregnancy Centers (CPCs) in the United States: Description of CPC Map Methods and Design Features and Analysis of Baseline Data. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(1):e16726. Published 2020 Mar 27. doi:10.2196/16726.